An iOS Game Post Mortem – Boom Boom Bros.

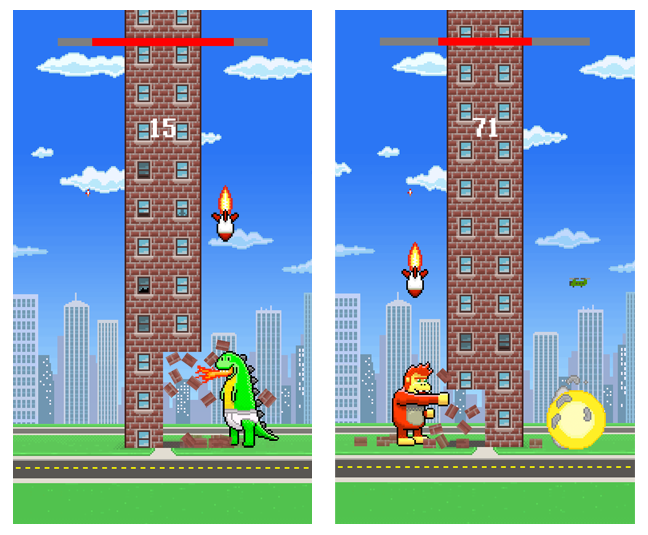

Boom Boom Bros is a Rampage inspired TimerMan-style game. Please check it out here, and give it a rating if you like it. Similar to Timberman, the player hacks away at a central structure, each hack replenishing the life bar which is slowly draining at all times. Unlike Timberman the obstacles, in the form of missiles, fall from the sky rather than being affixed to the side of the central structure. Additionally, the tower is composed of two sides. These attributes introduce a bit more of strategy in BBB. For instance, a wise player will hack as quickly during the early part of the game when the missiles are more sporadic.

Doing this fills up the energy bar for later in the game when the player is so busy dodging missiles that he/she can not easily hack at the building to keep that life bar up. Also, because the building is made up of two sides, the player can only hack so many segments on a side of the building before needing to flip to the other side. This causes the player to take risks when missiles are raining down, more so if the player’s life bar is low.

What Didn’t Work

Time Management:

BBB was developed in the evenings and on the weekends across the span of about 8 months. This was excessive for a game as simple as it is. An area where development could have been speeded along would have been in the offloading of the artwork. Doing all of the artwork (with the exception of the bricks tiles, which a friend fashioned for me) was a black hole of time. Animation, even the simple stuff in BBB, is mind bogglingly time consuming for me. Of course, I say this as if I didn’t love making all of those sprites; I loved it. However, if I was trying to make money off of an endeavor like this, and time was crucial, writing the code and rendering the artwork in parallel (via an artist) would have been the way to go.

A New Language & Framework:

Another aspect that extended development was that BBB was my first project written in Swift. I had previously spent a couple years writing iOS hobby projects in my spare time, followed by 2 years of experience as a full time iOS developer (starting sometime around iOS 5, and ending early during iOS 7’s reign). Those experiences made the learning curve pretty mild since I was familiar with the cocoa touch APIs. Regardless, development would have been speedier leveraging my experience in Objective-C. On the other hand, I can think of no better way to become familiar with a language than to use it in a project. I’d do it again, assuming time was not critical.

BBB was also my first game using SpriteKit. SpriteKit does a ton of great things for you, but I did encounter a handful of bugs that were nearly deal breakers. One notable one was where textures would disappear after animating through a set of them rapidly. I never solved this issue, but I did work around it. Another issue I had involved the inability to use certain sprites to formulate physics simulation collision boundaries. Like the previous issue, I couldn’t resolve the issue but was able to work around it. Yet another occurred when using Swift in conjunction with GameCenter. I’m sure that hiccup burned an entire day of time. Though each of these issues was relatively minor, the time spent debugging and working around each was significant. In hindsight I should have researched alternative frameworks for 2D games before starting in. Cocoas2D, for example, has been battle hardened at this point and I should have, at least, looked into it.

What Worked

Scope:

Keeping BBB’s scope extremely limited saved the project. Just getting this simple version released took 8 months. Without the discipline to draw boundaries between features for this first version and the next, I’d undoubtedly still be working on this game. There are things that are killing me that I would love to have incorporated into this game, but software is soft; I can add it later. Just getting it out the door, for me, was important to my sanity.

Easy Tweak-ability:

Architecture-wise the best decision I made was to make the game, character, background activity, achievement, and unlock configurations and graphics editable in a human readable plist file. Adding a new character to the game, after illustrating the character’s animation frames, takes minutes. Linking the character to an unlock, and associating it with an achievement is even easier. No code changes are required. It is definitely overkill for a game this small in scope, but doing things this way lowers the burden required to add new characters/unlocks/achievements … which means I’ll actually add new characters/unlocks/achievements. On a personal level building something elegant is rewarding to me. This aspect of the game is what I feel is the crowning achievement of the project; ease of configurability and expansion.

Graphics:

Pixelated retro-inspired graphics have been done to death in the indie development game world. That didn’t stop me, though. Scaling up smaller images made the app download size small. I also feel it was easier to keep the style of the game consistent when the graphics were so small.

Tools:

For major spans of the project I abandoned Xcode in favor of AppCode. Highlighting a variable/class in AppCode and doing a “find usage” operation is worth the price of admission alone. Xcode’s GUI editor is well done, but when it comes to writing code, AppCode is a productivity beast. It’s a shame I didn’t start using AppCode in earnest until after I stopped writing iOS software full time. Until just recently when Jetbrains moved to a subscription model, I was a full out JetBrains fanboy. In my day job I use CLion, and PyCharm non stop. I hate renting software, so I’m more lukewarm on Jetbrains these days, though I can’t deny they make excellent IDEs.

Test Driven Development:

I didn’t really build the core game using test driven development. It was not immediately apparent to me the path forward in unit testing SpriteKit related things that required timing, physics, actions, etc. I didn’t spent the time to figure out how to build a framework around my game to do as such. I find it to be an interesting problem to solve, but building the actual game was a higher priority. However, nearly all of the classes not tied into SpriteKit (via timing, collisions, etc) were written in a test driven manner. The biggest components included all the parsing utilities which utilized the human readable plist files that drove game configuration, characters, unlocks, and achievements. As a result of having a suite of tests, modifying the content and format of the human readable files (which essentially drive the game) is a non-event; when I run my tests I’m instantly aware of what I’ve broken. It’s a beautiful thing.

Overall, I’m happy with how it turned out. There are some things I would do differently if I were rewriting the app, but I’ve never finished a project without having that feeling.